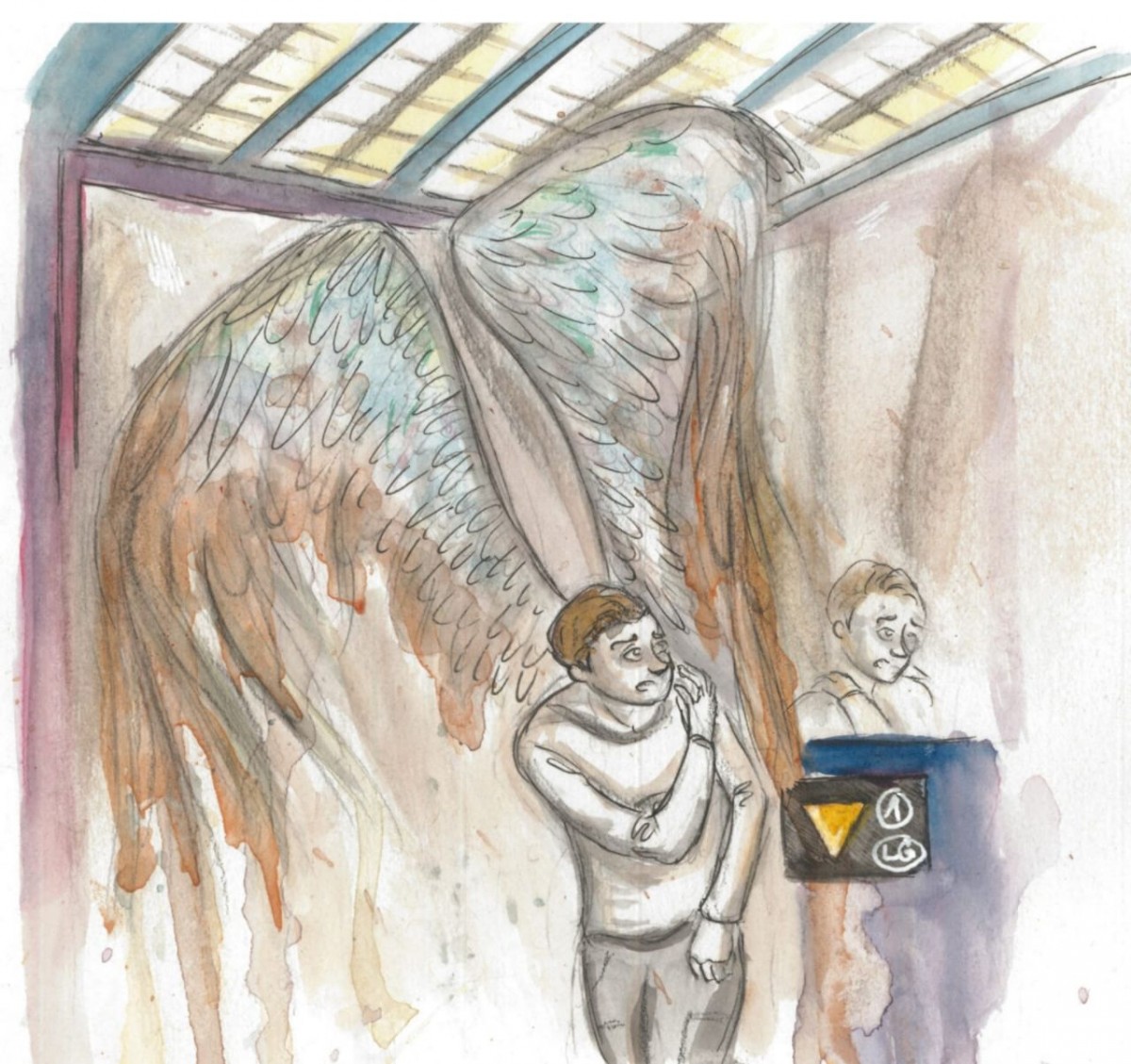

Image © Jeannine Bätz 2019

| by Josephine Bätz | December 5, 2019 |

The first time she dies, it is a practice run. Clinical, under lab conditions. It takes her a long time to come round again, and it hurts like hell. The assessment afterwards is curt and with all the unnecessary pleasantries removed, the body declared stable and ready for work. They send her down with a duffle bag and a pamphlet full of instructions. It hurts when she moves too fast; at this stage, the healing process still takes a while. They tell her it gets better with time. How long that takes will depend on her. Head office warns her that taking the wings out will be difficult at first; probably won’t work at all until she has rearranged some bone structures in the shoulder blades. She should hold off attempting until after the first few months, when the body is stable enough.

Down on the ground floor, she gets to work. The papers willed into existence on Sunday evening make her a nurse, and she fits in nicely. She doesn’t actually do much; but for some reason a lot of people survive their surgeries while she is on shift. With a few exceptions, of course; every morning, there is a ‘hands-off’ list with names waiting for her. When those people go into the operating theatre, she finds an excuse not to be in the same room. It is one thing not to question management (and she doesn’t). But she has no desire to watch. She holds that job for three months until people start to get suspicious.

The second time she dies, it’s a lot messier. But it only takes her half as long to bounce back. That’s some progress, says the HR guy while he watches her put the last few bones back in place and seal up a burst blood vessel. Maybe there have been reports about her time on earth, or he’s noticed that she watches herself in a different way. In any case, he signs her up for a further round of training. Therapy sessions he calls them, and she wonders what the therapy is supposed to be for. But she goes anyway, gives all the same answers to all the same questions, and lets the therapist drill the essentials into her head again.

The body is not your body, it is a thing. A machine molded by technicians, a tool to be used. It has to be killed a number of times in order to become stable. Don’t get attached to it.

When she comes out of the sessions, she buries herself in books about anatomy. Learns about every bone, muscle and blood vessel in the body; how it is constructed and how it can be healed. They send her back to the ground floor shortly afterwards, without a reprimand. She’s heard before that new field agents get away with a lot of things; apparently, it is true. Although permission to use her wings does get pushed back a few months – they want to wait until they are sure she can handle it. She doesn’t mind too much, there is no real use for them down there anyway. They get her a different job, but keep her in the medical profession. She is a doctor this time.

The third time she dies, it comes after a full year, which tells her she has been doing quite well. As does the fact that she has to put the body back together on the atomic level. It’s a test, and she passes it with ease. The performance review goes smoothly and they find a new job for her almost immediately. Only the commendation for strictly keeping to the lists of who and who not to save makes her queasy; there is a strange undertone to that part of the conversation. She talks about it with some of her siblings, and they tell her not to worry. But she can see that they are lying, and some keep their distance afterwards. As if they don’t want to be seen with her.

The first time she opens her wings down here she feels relief, like scratching an itch she has ignored for too long. She shakes them out and has a look in the mirror. The see-through feathers rustle like glass when she moves them. No one at the hospital saw the body die, so she goes back to her old job. She heals the patients she is supposed to heal and steers clear of everyone on the lists. She doesn’t leave the room anymore, though. And it bothers her less and less.

The fourth time she dies, it is after five years. She is almost relieved to be pulled out of this tedious job and eager for a new appointment. The body, subject to her medical expertise, heals in minutes now. But instead of the usual performance review she gets called to head office. She can sense something is wrong as soon as she enters the room. This is not a promotion. Sorry, they tell her, but you have come off the righteous path a while ago. See, the test wasn’t dying a few times. You have walked by adults and children alike and let them die indiscriminately. We are in modern times now, that attitude isn’t cutting it anymore. Have to keep up with the competition, you see. Unfortunately, we will have to let you go. On the upside, downstairs got a new manager. She is putting in some real effort, we hear.

In the lift downwards, she starts realising what has happened, but in a cold, detached way. It surprises her. The wings break out of her shoulders in an automatic reaction. In the steel wall she can see that they don’t shine anymore – the colour has turned to slime. When the feathers move, she smells a faint note of rotting blood. The lift stops.

___________________________________________________________________

Josephine Bätz is a student of film studies in Berlin, Germany, and writes poetry, flash fiction and short prose in English and German. She is the current student writer-in-residence for Berlin (2019). Poetry of hers has appeared in Josephine Quarterly.

Josephine Bätz is a student of film studies in Berlin, Germany, and writes poetry, flash fiction and short prose in English and German. She is the current student writer-in-residence for Berlin (2019). Poetry of hers has appeared in Josephine Quarterly.

Jeannine Bätz is a student of English and Russian Studies in Berlin and her art style mostly consists of urban sketching and illustrations. Recently published/ exhibited art projects of hers include a series of illustrations for Westermann Verlag and a Ukrainian-German art project organised by the Documentation centre for NS forced labour in Berlin and the KNUBA in Kyiv.

Jeannine Bätz is a student of English and Russian Studies in Berlin and her art style mostly consists of urban sketching and illustrations. Recently published/ exhibited art projects of hers include a series of illustrations for Westermann Verlag and a Ukrainian-German art project organised by the Documentation centre for NS forced labour in Berlin and the KNUBA in Kyiv.